The medium of Mughal miniature painting is defined fundamentally by its meticulous brushwork and narrative style. Rooted in South Asian visual culture, the art form flourished under the patronage of the Mughal emperors. Under their watchful eyes, court artists produced iconic and prolific works—paintings that did more than stylize royal life. They served to document, inscribe, and visually represent an imperial history1. From the Shahnameh and Jahangirnama to the Tutinamah, storytelling functioned as a powerful framework for authority and legacy.

Stories are essential components of South Asian culture — the very foundation of a region’s land and its people. On a more intimate scale, every family and individual carry their own stories shaped by lived experience. Ramzan Jafri, a Lahore-based miniature artist born in Quetta, deftly weaves storytelling through the needle of Indo-Persian miniature painting. In his exhibition, A Pattern of Pain and Love, he illustrates his years-long practice through textile fragments, textures, motifs and book spines that culminate into a reckoning with grief, loss, and violence. As the eye wanders across a large gauze-laden wasli, to a delicately illuminated empty book spine, Jafri prompts the viewer to ponder: Who holds the right to tell a story? And more quietly, what shifts when the marginalized are the ones to tell it?

As a graduate of NCA from 2012 in Miniature Painting, he has trained under numerous ustaads in Lahore. From learning bookbinding and archival conservation from the Fakir Khanam Museum in Lahore, to illumination techniques from an ustaad from Iran, he has devoted a considerable amount of time and care to traditional miniature techniques. Jafri generously doles out anecdotes of the trials of making a cat-hair brush, and speaking Farsi (his mother tongue) with his teachers. Spending a month or more on a piece, time is sacred to Jafri’s practice. He describes each step with fond excitement, speaking of the process as “holding the breath as he moves the qalam.”

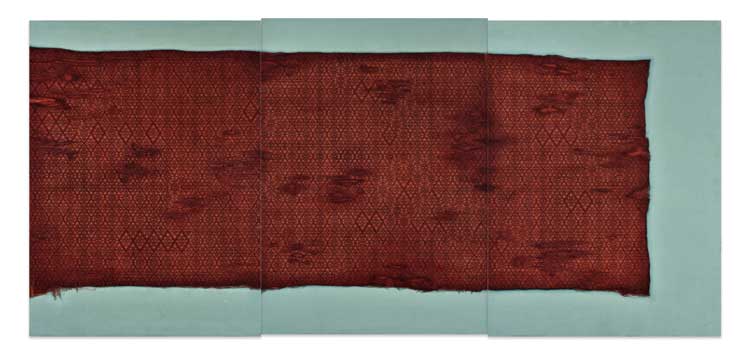

Care is indispensable to Jafri’s work. Torn to Speak depicts an expanse of surgical gauze collaged onto wasli. First, the gauze is laid delicately onto the surface with hand-made adhesive. Onto it, Jafri paints, with mathematical precision, the Qabtumar motif in repetition. The Qabtumar is an embroidery motif indigenous to the Hazara community, to which Jafri belongs. The interplay between traditional miniature techniques and gauze, a contemporary medium, is effortlessly quiet. From afar, the work reads as fabric. Upon close inspection, one is met with the texture of impossibly thin gauze, its strands fraying on the sides. Scattered across a field of crimson, reminiscent of oxidized blood, are pockets of erasure and friction. With these scars that tear the medium and the pattern, Jafri evokes a painful remembrance of the violence the Hazara community is subjected to, and has been, since the 1970s.2

In our interview, Jafri recounts his experience as a volunteer for an ambulance service in Quetta between 2006 and 2008, a period marked by a rise in targeted killings. His familiarity with gauze and bandages originates from these memories, later informing his choice of medium. With a gentle sensitivity, Jafri guides the viewer through the fragmented narratives of his community.

Through remnants, indigenous motifs, and an intentional treatment of material, he resists linearity and transparency in storytelling. Grief, memory, and loss, after all, are non-linear and opaque in themselves. As the Martinican philosopher Édouard Glissant argues, opacity is a right of the marginalized — a means of agency3. Jafri exercises this right with restraint and subtlety. In a similar quietness, glimpses of collars of shirts and hems of a kurti emerge across the room.

Various articles of clothing, obscured with a running lay of gauze as a sage field, disperse across the work. They melt into the gauze in moments, becoming a part of the land Jafri has laid down. These rendered details peek out vibrantly through muted green, suspended in time and memory. With such variety in form, one questions whom these collared shirts, kameezes, and dupattas belong to. The Qabtumar peeks out once again. In obscuring the mundane, these clothes are transformed into symbols of lives once lived, and what is left behind in the wake of violence. Amidst these subtle realizations, Jafri further utilizes the representational and the symbol in moments of directness— notably, the book spines.

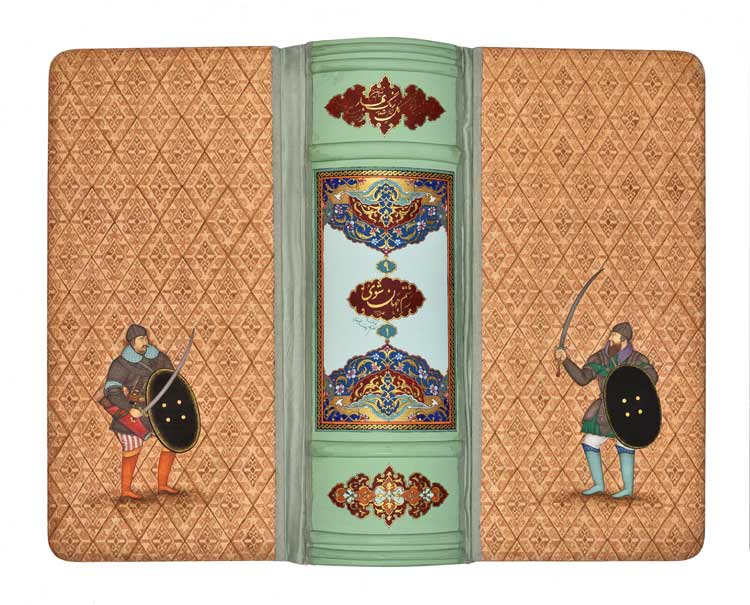

Rustam, a beloved hero in Persian folklore, is a frequently-depicted protagonist from the Shahnameh. In Rustaam-e-Jahan-Shavi, he is defined by the figure on the right and his title inscribed on the spine. Jafri, in a time-staking process, constructed the spine with wasli made from organic cotton paper. Ferdowsi describes the hero as elephant-bodied (pil-tan) 4, known for his strength and endurance. Similarly, Rustam is depicted by Jafri with a strong, alert comportment — a warrior situated in a field of Qabtumar. He brandishes his sword, ready to strike. The warrior who faces him is steady and heroic, possibly a member of Rustam’s cavalry. The power of narrative is exemplified in the book-cover form where these two men stand their ground. Their rendered shadows place them in the context of Jafri’s history and community. Beyond the recognizable icon of Rustam and the Qabtumar lies a motif embedded in the landscape of Jafri’s hometown, the Husn-e-Yousaf flower.

Where the warrior typically takes center stage on the cover, the shrub of Husn-e-Yousaf rests on the spine. With a colour palette of greens and reds echoed across the works, Jafri places the viewer in the physical and affective topography of his hometown. The flower, highlighted through name and composition, is one that grew in Jafri’s neighbourhood. Symbolizing a connection with the land, the shrub is enclosed in a boundary of bricks — the ghuncha. Blooming in protection, the site becomes a shrine for those lost in violence. By symbolizing the flower, Jafri further upholds the importance of non-human life, and its rooted connection with the people who are native to the land.

To create a symbol, to be the teller of a story, is a position of empowerment. Ramzan Jafri traverses these possibilities through dynamic interactions of contemporary media and forms with traditional miniature techniques. To symbolize is to memorialize, and perhaps, question existing structures of power. From nuance and opacity, through ruptures in gauze, to creating book spines anew with a resplendent warrior for his people, Jafri imbues his medium with the multifaceted human experience of grief, belonging, hope and loss.

A Pattern of Pain and Love was showcased at Chawkandi Gallery, Karachi, from 6th May to 16th May 2025.

Title image: Sukhan-e-Ishq, mix media and gouache on wasli,| 12 x 28 inches, 2018

All images © Ramzan Jafri, courtesy of Chawkandi Gallery. All rights reserved

References:

A Pattern of Pain and Love, Chawkandi Art Gallery, 2025. Catalogue.

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of relation. University of Michigan Press, 2024.

“Violent Persecution of the Shi’a Hazaras of Pakistan – UAB Institute for Human Rights Blog.” Sites.uab.edu, sites.uab.edu/humanrights/2021/03/17/violent-persecution-of-the-shia-hazaras-of-pakistan/.

Jafri, Ramzan. Interview. Eman Farhan. Monday, 26th May 2025.

Koch, Ebba. “Mughal art and imperial ideology: collected essays.” (No Title) (2001).

Maqsoodi, Ellaha, and Marina Bahar. “Exploring the Narratives of Rustom and Esfandiar Battle within Shahnameh Ferdowsi: An Analytical Evaluation.” Sprin Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences 3.4 (2024): 43-46.

- Koch, Ebba. “Mughal art and imperial ideology: collected essays.” (No Title) (2001).

- Mawani, Faiza. “Violent Persecution of the Shi’a Hazaras of Pakistan.” UAB Institute for Human Rights Blog, 5 Mar. 2021, https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/2021/03/17/violent-persecution-of-the-shia-hazaras-of-pakistan/

- Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of relation. University of Michigan Press, 2024.

- Maqsoodi, Ellaha, and Marina Bahar. “Exploring the Narratives of Rustom and Esfandiar Battle within Shahnameh Ferdowsi: An Analytical Evaluation.” Sprin Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences 3.4 (2024): 43-46.

Eman Farhan

Eman Farhan is a writer and artist from Karachi, Pakistan. They graduated from Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture with a BFA in 2024.Their work appears in Lakeer Magazine, The Blue Orange Project Magazine and other publications.

There are no comments