Most contemporary buzz words including— but not limited to— decolonisation, heritage, and culture are applicable to the show Tigers and Dragons: India and Wales in Britain at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea, Wales. At this juncture, a liminal threshold of contemporary art, culture and history, the question that begs answering is, what is decolonization? Is it simply a discourse on the past? Or a mourning of the losses of yesteryears? Is it knowledge sharing, shedding a light on past oppressions and their still-evident impact? Does it entail undoing widely-held perceptions? Is it demands for reparations; both cultural and monetary, evidently the only remit of the tragedy of the British Raj? How do we define Decolonisation?

In the case of Tigers and Dragons, an exhibition that showcases extensive visual cultural paraphernalia from both the past and present, decolonization is an effort to deconstruct and challenge prevalent notions on the role and identity of colonisers and reframe dialogue on the position of nations in a post-colonial global context. It includes works from contemporary and historic artists, pieces procured from around the UK, loaned from private collectors as well as borrowed from the Glynn Vivian’s permanent collection.

Art historian Zehra Jumabhoy, a Berger Trust Future Leaders Fellow in the history of British Art, and Curatorial Research Fellow at Glynn Vivian Museum— the role that culminated in this exhibition— has co-curated this show with Katy Freer. The showcase explores and develops new narratives that present imaginative and disruptive ways of seeing history while establishing unique connections. The premise is succinctly described on the Glynn Vivian website as investigating ‘visual symbolism of both Imperial subjugation— the Indian Tiger dominated by the Lion of Britannia and the Red Welsh Dragon pitted against the White Dragon of England— and national awakening.’ Included on the three floors of the gallery are over 100 artworks comprising paintings, photographs, performances, textiles, sculptural installations and new media, by roughly 70 artists from Wales, England, India and Pakistan.”

The works are divided into three theoretical premises; Historical Encounters: Tigers and Battles, Threshold Time: Bridges & Borders, and Myths of Nation: Wo(Men) & Mothers. In the first section, Tigers and Battles, power is investigated: the role of the Welsh in British Raj and the subsequent subjugation and ‘civilising’ of the colonised Hindustani populace represented through the metaphor of the taming/controlling of the Tiger. At the core of this concept is the Clive Collection from Powis Castle that makes a recurring appearance. Not least among the works showcasing the castle is Welsh-Indian artist Daniel Trivedy’s 2024 performance, documented through photographs, in which the artist, dressed as a tiger, roamed Powis Castle to reclaim a space that houses vast loot from pre-partition India—including wealth and artifacts belonging to Tipu Sultan, seized after his defeat in Mysore by Robert Clive, the castle’s original proprietor.

Similarly, drawing on references to Powis Castle, Clive of India, the Opium War of 1839, the unequal trade between China and Britain, and other lexicons of imperial power and resistance, is Adeela Suleman’s large-scale tapestry Imperium Amidst Opium Blossoms, commissioned specifically for this show. Paradoxically, this sixteen feet wide crimson silk, appliqued and embroidered piece that is stylistically akin to historic European paintings that sum of the conquests, atrocities and oppression committed by British Colonisers in a most visually aesthetic manner. With a depiction of Powis Castle in the back, Britannia in the forefront, the Welsh dragon and Tipu Sultan’s tiger side by side, together with an African page boy, all resting on a base of blooming opium flowers, it is a visual lesson out of a history book, composed on a single leaf, stacked and multidimensional like a miniature painting.

Displayed in the same space is a historic portrait of Robert Clive, borrowed from Powis Castle and an animation titled The Last Post by Shahzia Sikandar that portrays a caricature of Clive (or a company official) intruding/occupying a Mughal darbar before combusting into bits against a dark inky background in the final frame.

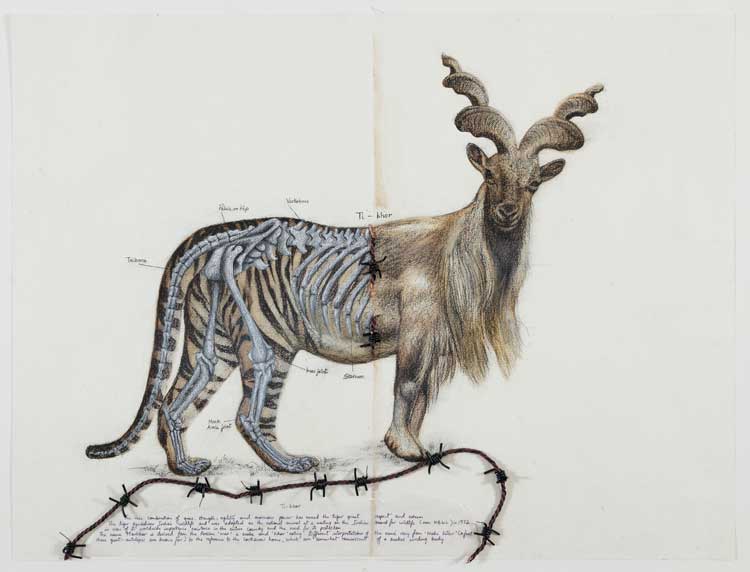

In the same theoretical space, where creatures like tigers and dragons metaphorically lock horns to compete, is Indian artist Reena Saini Kallat’s work which critiques the notion of symbols, marking territory through national emblems. She comments on shared history and loss through her work Hyphenated Lives (Ti-khor) portraying national symbols as hybrid forms. ‘Ti-khor is part of a series, a fusion of the tiger and markhor goat, the national animals of India and Pakistan. Though national symbols were meant to unite people from a region, they often become sources of contention as nations attempt to monopolise natural forms that don’t belong to either side.’ 1

The works clustered under the umbrella Threshold Time: Bridges & Borders hold the most amount of significance for anyone dealing with the persistent impact of colonisation i.e. the loss of identity, national-worth and pride, all a strategy and consequence of ‘civilising’ a people. It turns out cultural losses such as that of language (amongst other things), commonly observed in the elite-class of former colonies such as Pakistan, have echoes in places like Wales as well, where a loss of the Welsh language is felt even today as a direct result of Britain’s behaviour. This is best expressed in Tabernacl, a mixed-media drawing by Welsh artist Iwan Bala. Art from Pakistani artists like David Alesworth, Muzammil Ruheel, Liaqat Rasul, Anwer Shemza, Risham Syed converse with works by Indian artists like Zarina Hashmi, Reena Kallat within this space, thereby broaching, analysing and weaving a narrative honing in on the scars of colonialism, partition and loss.

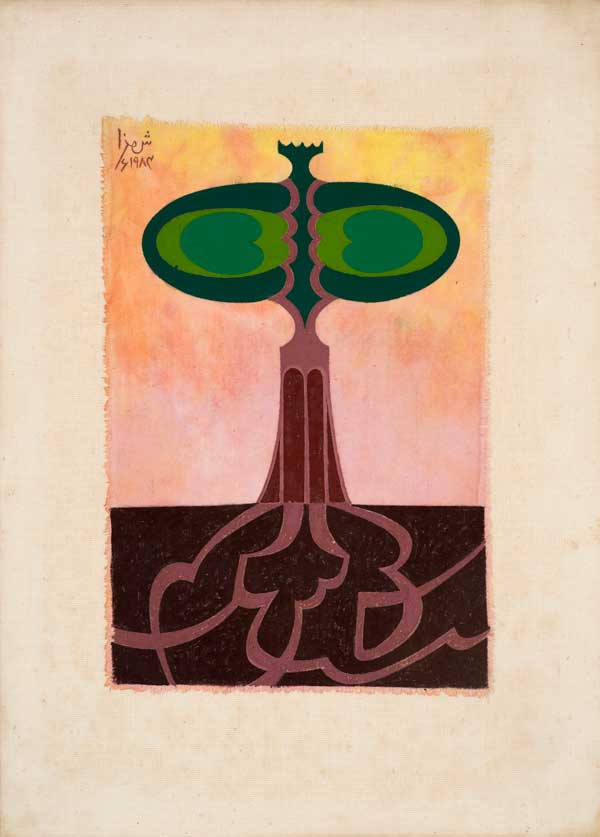

The loss of identity— of feeling unanchored, uprooted— is best reflected through two works of Anwer Shemza, who is flanked by Welsh artist Arthur Giardelli on one side and Muzzamil Ruheel on the other. Shemza’s Untitled modernist piece from the ‘Roots’ Series emerges from his desire to return to Pakistan. A symmetrical painting with a stylised tree at its centre has what appears to be Urdu script disguised as roots on the bottom half of the piece, except the script doesn’t form any words hence it is untranslatable, perhaps signifying the uprootedness felt by the artist, his desire to return to his home country which remained unfulfilled owing to his untimely death.

Juxtaposed alongside Shemza is contemporary practitioner Muzzamil Ruheel’s piece The Fallen Words. On an archival print of a traditional portrait of a Raja seated on a chair holding a hookah pipe, caught mid-action. Ruheel has intervened with his usual Urdu script in black acrylic partially concealing the raja’s identity and attire. This superimposition of Urdu text upon a nobleman’s portrait implies various meanings including the loss of and struggle for identity, of the birth of and belonging to a newly formed nation.

Nilima Shaikh’s Territorial Issues similar to her series Each Night Put Kashmir in your Dreams sheds light on the disputed state of Kashmir, a contentious remnant of the Raj, a wound still gaping to this day. On a powdery background in hues of blue, to the bottom right is a landscape of mountains and flowing water, on the opposite end, two animals that seem like Hyena’s composed in fine linework, interact. Flying above the scenic valley to the right, next to a whirlwind cyclone, executed in the same fine line are two mystical creatures bound to each with a single thread connecting their neck and feet. The wild beasts and the rocky terrain point to unresolved conflicts i.e., cultural and territorial divisions.

Displayed close by is Risham Syed’s piece titled ‘Texts and Contexts: Home’ which incorporates a 90-year-old photograph (circa 1935) of her maternal grandfather— an Income Tax Commissioner in the British Raj— with a map of London and Lahore. According to Syed, she aimed to connect past and present, contextualizing her Punjabi-Victorian upbringing in the work. Using tea washes, maps, and personal photographs the work attempts to navigate the complex relationship between colonial powers and the local populace. Nilima Shaikh and Risham Syed’s work is contextualised in the part of the exhibition that explores partition and home within the Threshold Time: Borders and Bridges remit.

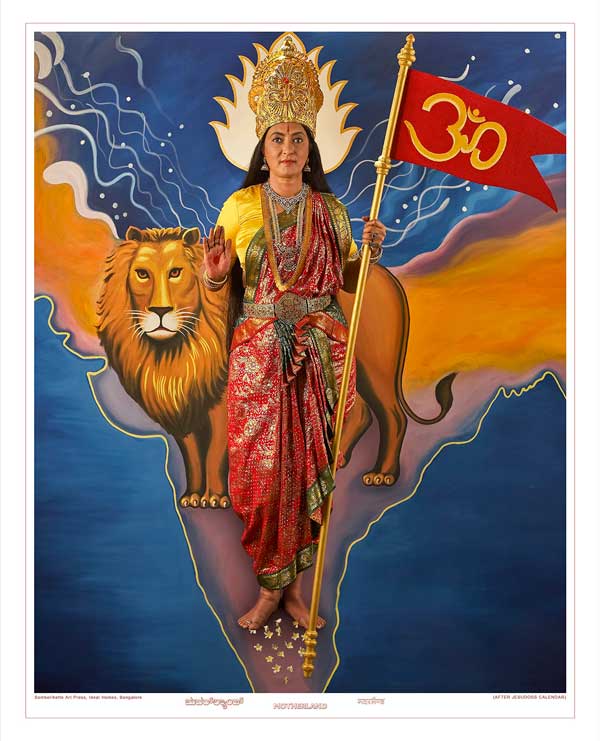

A final concern of this show elucidates a contemporary outlook considering women as synonymous with nations, presented under the theme of Myths of Nation: Wo(Men) & Mothers. Jumabhoy has juxtaposed the notion of Mother India with Mother Wales, another similarity between the two distinct and disparate geographical nations. Amongst other works, this is exemplified through Pushpamala N’s satirical piece Mother India, a giclee print appropriating commercial political photography titled Motherland, part of her Mother India Series (2014-2018). The work was ‘motivated by the ascendance of the Hindu Right and its manipulation of nationalist iconography’2. Pushpamala states she was “interested in looking at the history of ‘Mother India’ with the rise of fascism and fundamentalism in India. The Mother India-as-Durga figure was being used in right wing political rallies in a hyper-nationalist way3.

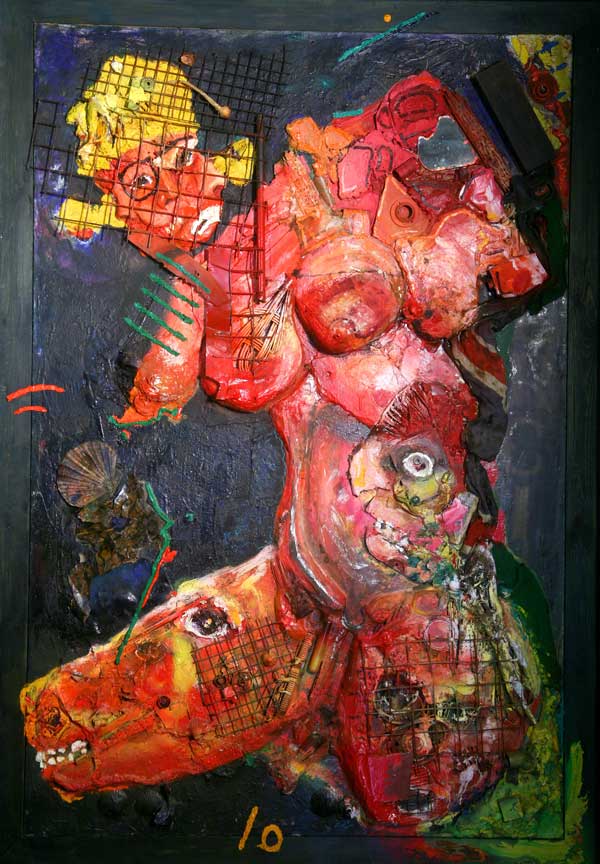

Akin to the concept of Mother India, exists Mother Wales, but unlike the all-consuming Mother India, the idea of Mother Wales signifies a devastated icon. Mother Wales is a symbol of resistance and struggle, a reminder of the atrocities committed to Wales. A bright and visceral mixed media painting by Welsh artist and member of the artist group Beca, Paul Davies ‘depicts the ravaged body of a woman and includes iconic Welsh imagery, for instance the Mari Lwyd, and on the Wales/ England border a hint of the Union Flag is seen. This political artwork is an illustration of the issues Wales has confronted and is still confronting.’ (Barry Plummer, Bloomberg Connects). This piece references the Rebecca Rioters of 1839-43, a significant historic Welsh group that rebelled against the English and the taxes they imposed on the already struggling Welsh farmers.

In this latest curatorial offering Jumabhoy sheds light on Wales, which despite its role in the imperial expansion of British Raj in undivided India, was simultaneously a victim of English oppression. Through a contemporary lens, Jumabhoy’s curatorial endeavour investigates symbols such as tigers, attempting to take ownership and decolonise through works of artists like Faiza Butt and Amna Walayat, she explores the impact of colonisation on home, territory and identity through artists’ work like Iwan Bawa, David Alesworth, Zarina Hashmi, Liaqat Rasul and Reena Saini Kallat and wraps it up with a particular focus on womanhood/nationhood through works like that of Nalini Malini and Christopher Williams.

As expressed in the curatorial description, contrasting the Tiger of India with the Dragon of Wales, forges a new connection and new way of seeing the role of Wales in the colonisation of India, bearing in mind Wales’ own humbled position in Britain. Despite that it does not undermine the role of the Welsh in the subjugation and theft of culture and artefacts from un-divided India, instead it calls out its culpability and implicates Wales.

Curated by Zehra Jumabhoy and Katy Freer, Tigers and Dragons: India and Wales in Britain, is up at the Glynn Vivian Gallery in Swansea from 23rd May to 2nd November 2025.

Title Image: Faiza Butt, My Love Plays in Heavenly Ways, 2013, Ink on polyester film, 121×151.6cm. Image courtesy the artist.

References

Arts, India News, Press Reader 07 June 2025 https://www.pressreader.com/uk/western-mail-weekend/20250607/281741275366477

Bloomberg connects, https://guides.bloombergconnects.org/en-US/guide/glynnVivianArtGallery/exhibition/288c7be3-0f2c-4d5f-907e-d06156ce5a47

Interview Zehra Jumabhoy, 17th July, 2025, London

Andrew Green, July 11, 2025, Gwallter, Tigers and Dragons https://gwallter.com/art/tigers-and-dragons.html

Jumabhoy, Zehra, website, https://www.zehrajumabhoy.com/curating/

Sanjana Ray, 5 June 2025, GQ India, Inside Tigers & Dragons, a unique art exhibition that explores the historic connection between India and Wales in the context of British Imperialism, https://www.gqindia.com/content/inside-tigers-and-dragons-a-unique-art-exhibition-that-explores-the-historic-connection-between-india-and-wales-in-the-context-of-british-imperialism

Trivedi, Daniel, website, http://www.danieltrivedy.com/a-tiger-in-the-castle.html

Zehra Jumbhoy, Curator’s Concept.

- Bloomberg Connects, https://guides.bloombergconnects.org/en-US/guide/glynnVivianArtGallery/item/a014d245-0289-4eb7-aa74-d1b3e63364ba

- Bloomberg Connects, https://guides.bloombergconnects.org/en-US/guide/glynnVivianArtGallery/item/0040e02d-1324-40ab-8068-2e92f5ecd575

- Bloomberg Connects, https://guides.bloombergconnects.org/en-US/guide/glynnVivianArtGallery/item/0040e02d-1324-40ab-8068-2e92f5ecd575

Samar F Zia

Samar F. Zia is an artist, curator and writer based in London. Besides being a mother artist and maker, she authors critical essays examining cultural markers such as art and books. Zia holds an MA FA from Central Saint Martins, London and graduated with Distinction in BFA from Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi. She regularly contributes to her Alma Mater UAL’s Alumni of Colour Association (AoCA) by curating exhibitions and events. She has been artist-in-residence at the Fitzrovia Community Centre where she curated multiple exhibitions. She is also a Trustee of the Fitzrovia Chapel. Zia is founder of Art Social where she facilitates bespoke creative workshops for youth groups and adults for various institutions across London. Zia regularly exhibits in both Pakistan and the UK. Zia has also participated in art fairs in UK such as the Affordable Art Fair and Fresh Art Fair. Besides being an independent curator and workshop lead, she has worked as Exhibition Guide at the Hayward Gallery. She has served as visiting faculty at Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi and taught at Art Academy London.

There are no comments