Not Ali Imam

The mother of three boys, Zohra Husain, has passed the mantle to her youngest son, the affable Dr. Haider Husain. As director, he now steers the gallery through a transformed, post-pandemic art world— where online viewing rooms have partially replaced openings with tea and nibbles— Haider navigates a new era of curators, collectors, and marketing.

Despite a series of personal tragedies Zohra courageously made Chawkandi the most respected, and longest running art gallery in Pakistan. But it wasn’t easy breaking into the boy’s club of the art scene. Ali Imam was a towering figure of Pakistan’s Modern Art movement— a mentor who nurtured collectors and brought together poets, artists, and writers, with many major collections born from his Sunday salons. Zohra credits him for creating an atmosphere conducive to art sales and establishing a nucleus of buyers. But as Niilofur Farrukh mentions, “Zohra didn’t try to be Ali Imam.” She was clear-eyed about her role: this was a business, but one that demanded excellence. So, she brought something uniquely her own— something best described by the word synonymous with Zohra’s birthplace: tehzib. Often translated as “refinement,” tehzib is richer— blending civility, erudition, and urban grace. It captures the cultural soul of Lucknow, a city known to inspire loyalty and wistful longing.

Graceful and poised, Zohra held court, whether at the gallery or at dinner parties in her home with its arched doorways. After meals, she would present a silver khaasdaan draped in red cloth, offering guests freshly made paan attached by delicate silver chains. Her breezy, conversational style put people at ease— at the gallery, you felt like a guest, not a customer. From an ‘art outsider’, she became, according to British Art critic and artist Gregory Minissale “an intriguing mixture of businesswoman, elegant socialite, and artistic patron”, with a “warmth and modesty.” She is one of the few gallerists to make phone calls thanking writers when they cover a show.

The 80’s

Under the stifling climate of General Zia-ul-Haq and the marginalization of women’s contributions, Zohra Hussain boldly opened her gallery’s doors in September 1985. “I had a shop in Clifton— I felt it looked like a gallery; it was a long strip”. Sculptor Shahid Sajjad, who would become one of Chawkandi’s greatest allies, was incredulous: “Waqai aap gallery bana rahi hain?” (“You’re really making a gallery?”) He mentored the young Zohra— introducing her to artists, showing her New York gallery print materials so she could grasp the vocabulary and the mechanics of running a gallery, and bringing collectors and guests to her doorstep. When the contractor proudly constructed a decorative roof, Sajjad ordered its removal: “Koi chhat dekhne nahi aa raha, paintings dekhne aa rahe hain.” (“No one’s coming to see the ceiling, they’re coming to see the art.”) Zohra, in turn, always acknowledged his support. In her signature casual style, she’d often drop Shahid Sajjad’s name, alongside Zahoor ul Akhlaq’s and Anwar Saeed’s, when chatting with guests and buyers.

The physical and spiritual turmoil of the 1980s shaped artists like Meher Afroz, whose Mask and Puppet series hung on Chawkandi’s walls in 1987, to much acclaim. Zohra was initially hesitant to promote Meher Afroz, a relative, but soon treated her like any other artist. It was Afroz who gave Chawkandi its name, taken from her former studio.

Ali Imam’s Indus Gallery operated out of his home— visitors might catch glimpses of his children doing homework. Zohra Hussain saw this informality as an opportunity. Her gallery was carpeted— a fashionable touch in the 1980s— there was air conditioning and thoughtful lighting. Clifton was less inhabited then, around the gallery “there were no cars or buildings— just kabootar.” People would wander in from the supermarket downstairs while their wives shopped. “I’d take them around and talk about art. They weren’t intimidated by me.” Ever the gracious host, she served coffee and tea all day to visitors who came as much to talk as to see the art. As Niilofur Farrukh recalls, “Zohra Apa would talk to you— she didn’t care if you were a buyer”.

Ali Imam’s model focused on making art cheap and accessible, a philosophy many artists opposed. In 1985, a Shahid sculpture priced at Rs 9,000 at the Indus Gallery sold for more than twice that amount after Zohra placed it on a “nice pedestal” with a spotlight, proof that presentation could be transformative. Artists were also drawn to Zohra’s approach: she didn’t quibble. Shahid Sajjad and Zahoor ul Akhlaq never showed with Indus Gallery due to creative differences, Jamil Naqsh also had a falling out with Imam. Women artists like Naheed Raza and Qudsia Nisar found it difficult to work with him. Zohra gave them all a space. She recalls the nervousness of a young Qudsia Nisar, in Chawkandi’s early days, “If this gallery doesn’t work, what will Ali Imam do to us?”

Aesthetic sensibility

Zohra’s cultural sophistication (in Niilofur Farrukh’s words) stemmed from both her Lucknawi upbringing and Shia heritage. “Our roof would be covered in over 150 diyas” she recalls for the celebrations of 13 Rajab, Hazrat Ali’s birthday. Muharram, in Lucknow was unique, “I remember a yellow alam, it was my favourite. At the start of Muharram, everyone took part in choosing taziyas;” as Zahoor ul Akhlaq once noted, the taziya is a sculptural achievement of the subcontinent.

In June 1947, while vacationing by Nainital lake, an 8-year-old Zohra’s parents were moved when they heard Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s voice on the radio. By December, they migrated, traveling by boat from Bombay to Karachi. Her mother disguised herself during the journey, by draping her sari “like a Hindu.” As they neared land, passengers tossed their Hindu caps in the air, chanting Naray Pakistan! The youngest of three, Zohra remembers being lifted from the boat onto the shores of a newly born Pakistan.

Zohra’s roots and experience of displacement forged a deep bond with artist Zarina Hashmi, introduced to her by Marjorie Husain around 1985. “Her work was so elegant, and we had so much in common,” Zohra recalled. Zarina remained fiercely loyal to Chawkandi throughout her life. Her prints captured subtle elements of the subcontinent: afternoons with hot lu winds, or the scent of water sprinkled on woven khus screens made from tropical grass to cool the room. Zarina was dismissed by Ali Imam, who saw no market for prints, yet her shows at Chawkandi consistently sold out.

A new art economy

By 2011 in cities like London, young artists were fetching skyrocketing prices in the secondary (or resale) market, a space historically for ageing or dead artists. Worldwide, the “heat around contemporary art” birthed a new kind of art economy, and a new species, dubbed “specullector”, a fusion of the art collector and dealer/speculator. Globally there was big money around art.

The “heat” for contemporary art reached Pakistan in December 1997, and recent NCA graduated miniaturists held their first major group show at Zohra Hussain’s invitation. Featuring artists like Imran Qureshi, Talha Rathore, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Sumaira Tazeen, Aisha Khalid, Fasihullah Ahsan and Amina Ali, this event marked the birth of the contemporary miniature movement, hailed as Pakistan’s first home-grown art movement and Chawkandi was the hub from where it took flight. “Everyone was talking about that show,” Zohra says “shaadiyon pey bhi” (even at weddings). It may have compensated for the regret she felt when she just missed a young Shahzia Sikander before she left for the United States.

“Last week a Zarina Hashmi sold for thousands in auction”, she remarked in 2014— now I’m getting calls for a Zarina Hashmi!” Lamenting the shift from passion to prestige, she says “People used to buy art for love. Now they all need a Naqsh. They are all competing with themselves.” One of her dearest friends, the late architect Habib Fida Ali, never cared for names— only beauty. A year before his passing, he showcased his eclectic collection at Chawkandi in Journey of Passion— from Company paintings, gorgeous silver objects, even a bangle-cuff bought during his travels, displayed like a sculpture on a pedestal— it was a lesson in art sparking joy.

Heyday

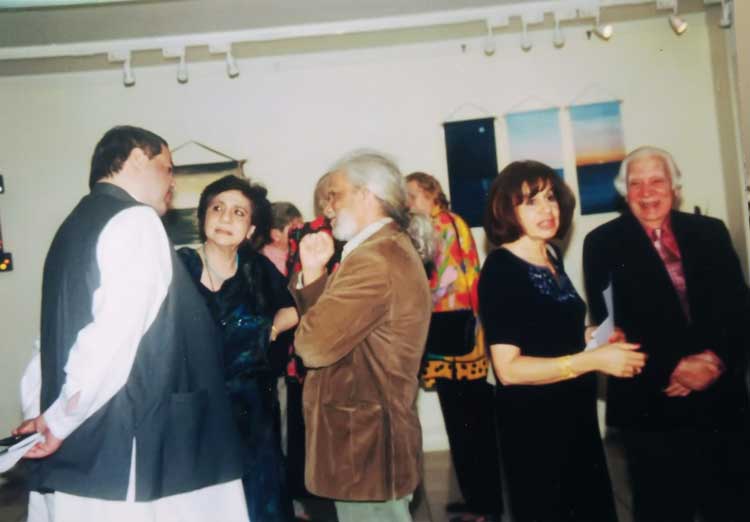

On the cool evening of March 12, 1991, Zohra Husain, elegant in her sari, stood amongst Samina Mansuri’s paintings. There was energy in the air, a spark that would continue to burn for over a decade for Chawkandi. ‘You dressed up for an opening at Chawkandi, it was a big deal’, one attendee recalls. Artists often waited years for a chance to exhibit there, says critic and curator Amra Ali.

Resplendent, Zohra Hussain would preside as the gallery buzzed with energy. Shahid Sajjad’s groundbreaking My Primitives show in 1994 drew “heavy-breathing art grandees, ” women with pearls, men with pocket squares. Mansuri (the finest draughtsperson in Pakistan according to Dr Naqvi) was creating exciting new paintings; you could sell a Askari Mian Irani for 50,000 rupees.

The calendar was packed with landmark exhibitions, Colin David’s 1992 show featured two figurative nudes, his first public display after a period of cultural censorship. For Zahoor ul Akhlaq’s solo, the paintings were finished so late he brought them to the gallery unframed, Shahid Sajjad spent the night in the gallery, cutting and welding metal as sparks flew, to help hang the show. The next day television crews and guests were at the opening, but the two artists slept through it.

On regular days, artists and creative personalities would assemble at Chawkandi. Dr Akbar Naqvi made appearances, Qudoos Mirza, as well as Habib Fida Ali and Zahoor. Zohra handpicked whom she “gave a wall to”. “I used to drop commission for artists like Zahoor ul Akhlaq, so they’d be encouraged. Some were difficult to sell, but I believed in them”. She would speak to artists, “trying to look inside their minds— does it seem like they have a lot of material? I would check if girls were married, if they have supportive husbands.” Salima Hashmi would send talented NCA artists her way, and Zohra would invite Newsline’s editor Rehana Hakeem for dinner parties. In return Rehana would have to fend off criticism of giving Chawkandi the most coverage. Years ago, while cleaning out her drawers, Zohra came across a pamphlet from a young artist seeking an exhibition— his name was Rashid Rana.

Zohra Apa. Mrs Husain.

As an art world outsider, Zohra put in the legwork— flying to Lahore to visit NCA, or trekking to Ismail Gulgee’s home to secure paintings for clients. She played a vital role in helping artists sustain their livelihoods in the absence of institutional support. In Karachi, she was among the few trusted gallery owners who could authenticate works, thanks to her deep relationships with artists and meticulous records.

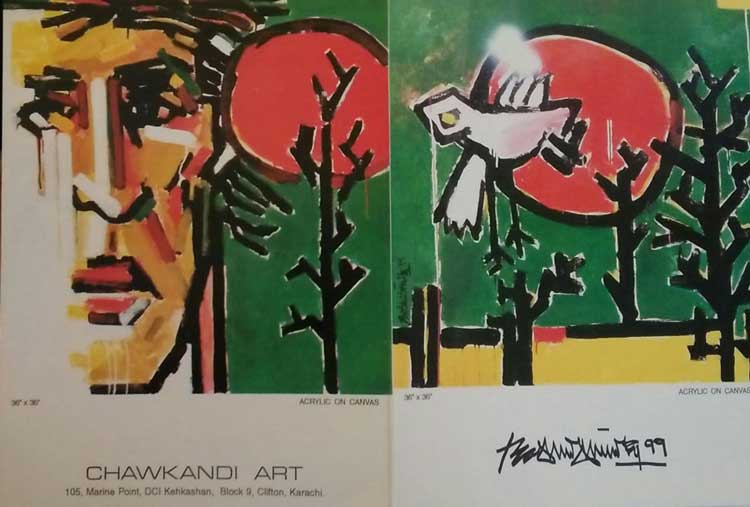

It is a delight perusing Chawkandi’s extraordinary archive— yellowing newspaper and magazine clippings, photographs and invitation cards ‘Chawkandi Art takes great pleasure in inviting you to an exhibition of latest ten paintings by Bashir Mirza.” A smiling Shahid Sajjad amidst his graceful sculptures, Summaya Durrani’s menacing flowers on the wall, a girlish Sheherezade Alam showing a pot to Zohra in her chundri sari. Even PIA once sponsored art exhibitions. And then Zohra herself— her memory is a marvel. She seems to know everyone, and their grandparents too, lacing anecdotes with Urdu literature and poetry.

Zohra created this atmosphere, where there were conversations and historical contexts. Artists like Meher Afroz protested in the streets then returned to the studio to translate that fire into form (Mein Hazara hoon series in 2014). Now, art often moves quietly through auctions, back rooms, changing hands without any interaction with the artist. The world has changed, where is someone like Zohra Husain’s place in it? The late Herald editor, Saquib Hanif, once reflected on her legacy during an interview, saying, “Hum sab ko bara kuch sikhaya hai” (She has taught us all so much). He called her Mrs. Husain, explaining “Mein unko Zohra Apa kehnay ki himmat nahin karoon ga, kyunaky wo hum sab ki bari hain” (I won’t dare to call her Zohra Apa because she is an elder for all of us). The iron fist in the velvet glove— and silk sari— remains beyond compare.

Written in tribute to Ms. Zohra Husain, founder of Chawkandi Art Gallery, the longest-running gallery in Pakistan, on its 40th anniversary.

Title image: Zohra Husain and Maqsood Ali at Chawkandi’s earlier premises in the late 80’s.

All images are courtesy of, and copyrighted to Chawkandi Art Gallery.

Fascinating piece of writing Zehra, congratulations. Well research article that sheds light on how Zohra Husain carved out a path for herself in the art scene of Karachi. Much deserved tribute to a lady who provided space and guidance to many artists and collectors. I loved the parallels in style and characteristics between Ali Imam and Zohra Husain that you shared. Thank you.