Historical retellings of modern art from Western perspectives trace the origins of text-based image making at the beginning of the 20th century. Referring to American consumer culture, influential critics such as Lucy Lippard, W.J.T. Mitchell, and Hal Foster often discussed Spanish painters Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque’s use of newspaper fragments in collages and American artist Edward Ruscha’s work with typography. Then there is American artist Robert Indiana’s LOVE (1964) sculpture, which transformed a word into a visual icon, serving as a foundational example of text-based conceptual art.

However, these West-centric discourses overlook the vast history of calligraphic art that has spanned several centuries in South Asia and the Middle East. The significance of text-based visual art, specifically those involving animal shapes and its influence on ornamental aesthetics, were integral in defining the socio-cultural contexts of the MENASA region. Some historical examples include animal-shaped Kufic inscriptions in Seljuk Iran, to the “Lion of God” pictorial calligraphy in Ottoman scrolls (circa 1458).1

Contemporary artists invoke similar aesthetics of decorative text in their works to redefine what it means to appropriate historical script. Trained in calligraphy, Muzzumil Ruheel’s two-decade oeuvre connects a cohesive thread from the origins of his earliest renditions of calligraphy to his most recent body of work. His interpretation of the genre of calligraphic art dismantles traditional notions of the medium, thus challenging the meaning of not only the words but the medium itself.

Growing up in Punjab, Pakistan, calligraphic script inspired from sacred texts like the Quran, regional cinema, and the day-to-day social influence of culture and religion attuned Ruheel to different forms of visual creations. He witnessed the role of traditional calligraphers in the printing press and cinema posters before the mainstream usage of digital processes rendered the traditional calligrapher’s skill nearly obsolete. Whether he was discussing “ghost words” like those in Meeting Point (2022) or avoiding certain words altogether due to censorship like in Choose Your Words Carefully (2023), Ruheel has recreated the form and meaning of the visual language of Urdu words. His earlier work from the Lollywood (2003) series presented titles of Punjabi films like “Maula Jutt” in the aesthetic of traditional calligraphy. (Funnily, in a conversation, the artist told me that this went completely unnoticed to viewers— even those belonging to the Islamic scholarly circle— who observed the artwork as Arabic words comprising Quranic verses instead of what it was representing).

In zoomorphic calligraphy, the most cited purpose of shaping religious texts into animal forms is to avoid conventional figurative imagery, thereby adhering to orthodox Islamic restrictions observed in some Islamic contexts. However, the use of intricate designs for patternmaking and storytelling in decorative arts from Islamic lands is often over-simplified. In his essay, “The Content of Form: Islamic Calligraphy between Text and Representation,” Turkish historian Irvin Cemil Schick writes: “Calligraphic images are, in a way, akin to an x-ray image that exposes the normally invisible skeleton, which is in truth the supporting scaffolding of the human body, without which the latter would collapse.” 2

Ruheel takes a similar approach to his designs that use the idea of the invisible meanings in words as the basis of his zoomorphic structures. These words inscribed are not meant to uphold religious sentimental values but expose words that are often whispered under one’s breath sarcastically in the common vernacular. At first glance, the script inscribed within the animals in the zoomorphic designs seemingly fulfils a decorative purpose, such as those found on rock crystal ewers from Fatimid Egypt (10-11th century) 3 Upon closer inspection, each artwork’s title can be located within the script, intricately woven into the contours of the creatures. The zoomorphic designs have been carefully selected based on what purpose they may lend to pictorial representation. Using the Thuluth script—originated during the early Abbasid period in the 7th–9th centuries CE and evolving from the earlier Kufic and Naskh scripts mainly used in inscriptions and mosque decorations,4 —the Urdu translation of each title is seen fluidly integrated into the outline.

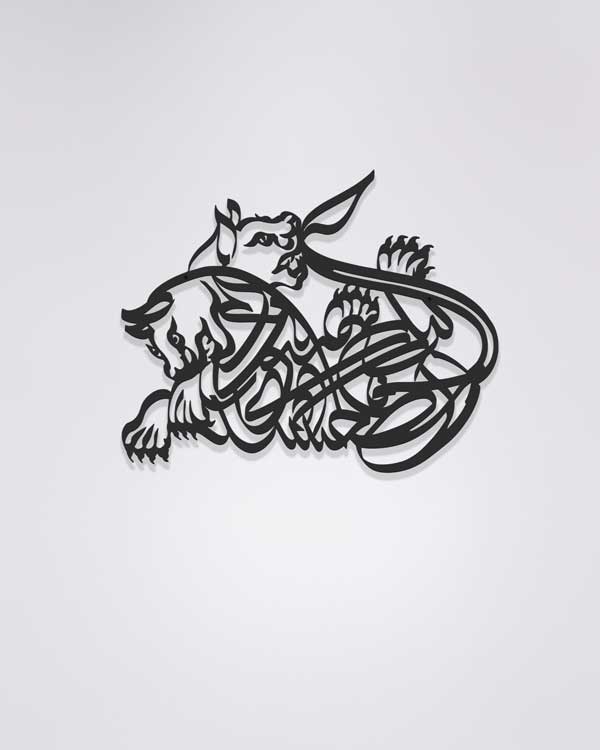

In Mute? Not Today (2025), a deer is hung upside down as though its legs were tied together with an invisible rope. The relationship between the hunter and prey is immediate. Commenting on the political state of censorship in the country, Ruheel sees the deer as analogous to journalists being forced into silence. He also intends this work as a comment about the deaths of Palestinian journalists, since the Palestinian genocide commencing October 7, 2023, at the hands of the Israeli military forces. At least, 241 journalists and media workers have died according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).5 Though the deer may look hunted and preyed on, the Thuluth script spells out a different meaning: Khamosh Nahi Bethon Ga Mai – I’m not staying silent.

Other works comment on smaller incidences of passive-aggressiveness in social settings. In Can’t Argue With Genius, we see the Urdu words Ji App Sahi Keh Rahey Hain curved into the shape of a fish. The not-so-subtle meaning behind this sarcastic statement is understood by many Pakistanis who have ever tried to escape an argument, withheld their actual thoughts, or expressed the opposite of what they were feeling. Ruheel sees this as representative of a slippery conversation, one that cannot be held and simply escapes from one’s hands.

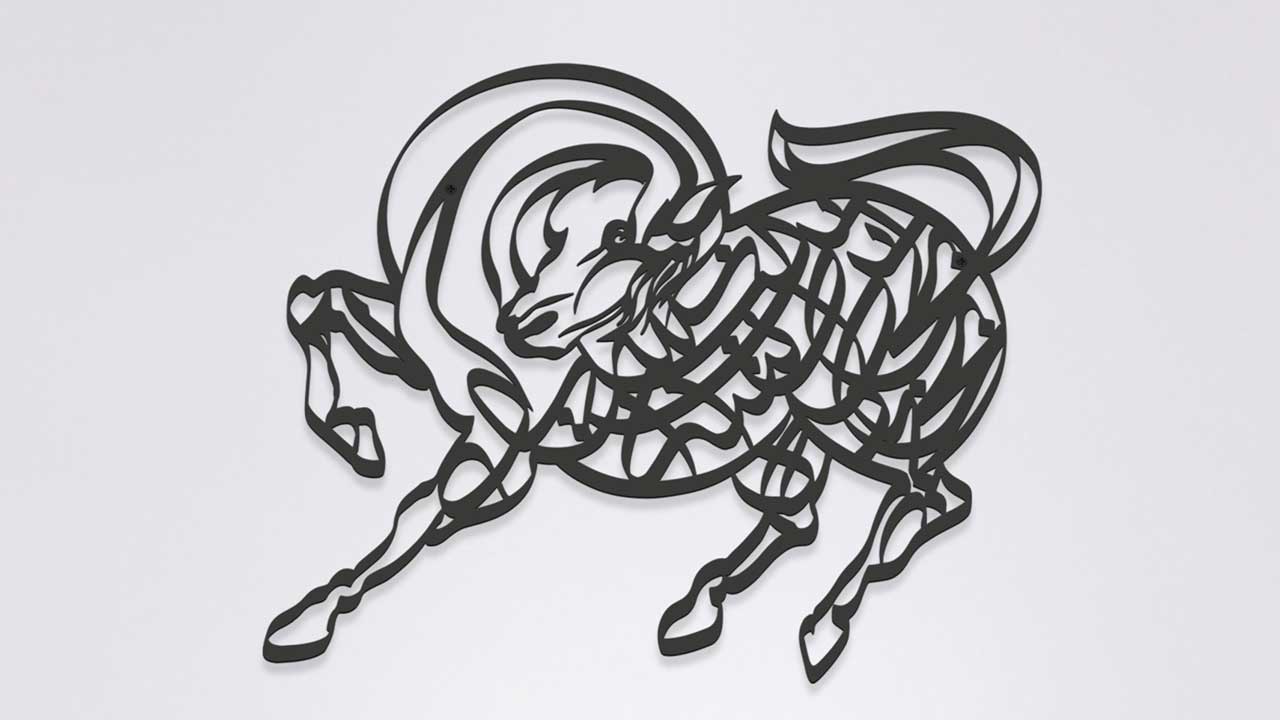

Similarly, in Why So Pleasant? Ruheel uses commonly used taunts in Urdu to foreground insincerity found in certain conversations. The sarcasm behind Itna Muskura Ker Kiyoon Khitab Ker Rahay Hoo (translated to “Wipe that fake smile off”) (2025) is presented as a two-headed lion that represents double dealing. He curves the Urdu alphabet “س” into the lion’s paws and leg, crafting the entire sentence into one contour. Another attempt at pointing out sarcasm in daily vernacular, the work Grand Entrance (2025) depicts a horse mid-gallop. Entering while riding a horse has historically been symbolic in South Asian ceremonial practices: particularly in royal, military, and matrimonial contexts. The written text being Taalian bajain? – app tashreef le ain hain translated to “Let’s all give a round of applause, you finally decided to show up,” highlights the taunting way of addressing specific annoyances at someone’s tardiness, while symbolizing their “grand entrance” through the historical significance of a horse.

Different variations of birds, a dog, and an alligator get featured amidst a catalogue of statements and satirical comments which almost act as an etymological collection of current Urdu vernaculars. Initially drafted as digital designs on a tablet and then transformed to physical installations in steel, Ruheel bends the traditional notions of zoomorphic calligraphy to fit evolving methods of the craft. The artist does not shy away from modern mediums of artmaking, having previously also created works in augmented reality outside of the traditional gallery setting. Ruheel continues to choose words and visuals that go unnoticed in daily settings, whether in the form of hidden meanings in sarcastic comments, or invisible words whispered between sentences.

“The Wild in Our Mouths” by Muzzumil Ruheel was on display at Canvas Gallery from 16th – 25th September 2025.

All images are courtesy of Canvas Gallery.

Title image: Grand Entrance (Taalian bajain? – app tashreef le ain hain

Let’s all give a round of applause, you finally decided to show up), paint, mild steel, screws, 18 x 14 x 1 inches, 2025.

Bibliography

Bedos-Rézak, Brigitte M., and Jeffrey F. Hamburger, eds. Sign and Design: Script as Image in Cross-Cultural Perspective (300–1600 CE). Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2016.

Blair, Sheila S. Islamic Calligraphy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006.

Committee to Protect Journalists. “Journalist Casualties in the Israel-Gaza War.” Last modified October 22, 2025. https://cpj.org/2024/11/journalist-casualties-in-the-israel-gaza-conflict/.

Dallas Museum of Art. “Rock Crystal Ewer (Keir Collection).” Accessed February 12, 2026. https://dma.org/art/exhibitions/rock-crystal-ewer-keir-collection.

- Brigitte M., Bedos-Rézak and Jeffrey F. Hamburger, eds., Sign and Design: Script as Image in Cross-Cultural Perspective (300–1600 CE) (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2016), 184.

- Sign and Design, p 186.

- Dallas Museum of Art, “Rock Crystal Ewer (Keir Collection),” accessed February 12, 2026, https://dma.org/art/exhibitions/rock-crystal-ewer-keir-collection

- Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006).

- Committee to Protect Journalists, “Journalist Casualties in the Israel-Gaza War,” last modified October 22, 2025, https://cpj.org/2024/11/journalist-casualties-in-the-israel-gaza-conflict/

Noor Butt

Noor Butt is a Pakistani artist, writer, and educator based in Canada. Her professional portfolio includes the Karachi Biennale Trust, Vasl Artists’ Association, and Qatar Museums. Recipient of the Inception Grant by Art Incept, she has been published in ArtNow Pakistan, The Karachi Collective, and Hybrid - Interdisciplinary Journal of Art, Design, and Architecture. She has taught art history courses in the Liberal Arts program at IVS, and currently works as an Artist Educator at ‘Arts for All’ in the Hamilton Conservatory for the Arts, ON, Canada. She holds a BFA from the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, and an MA in History of Art from the University of London, Birkbeck College.

There are no comments