In the ever-evolving terrain of contemporary South Asian art, the work of Ghulam Mohammad also known as GM, emerges as a meditative and materially intricate inspection of language, identity, and memory. A recipient of the prestigious Jameel Art Prize in 2016, Mohammad is widely celebrated for his laborious and mesmerizing paper collages. Mohammad’s practice radically recontextualizes text, both as a cultural signifier and as a visual form. His work does not merely use language as a medium, rather it questions the very conditions of legibility, meaning-making, and cultural erasure that surround it.

The foundation of Mohammad’s practice lies in deconstruction, a methodological dismantling of written language. His process of slicing Urdu text into individual letters or syllables and then rendering them unreadable aligns conceptually with Jacques Derrida’s theory of deconstruction, which imagines that language is inherently unstable, always differing and deferring meaning.1 He suggested that ‘structures’ were to be undone, decomposed and disseminated. This is exactly what Ghulam Muhammad does through his works exhibited in his recent show titled Taleef. He plays with language and its structures, using script as his tool. By obscuring readability, Mohammad separates text from its immediate semantic role, having his viewer experience it as form rather than message.

This disruption offers a critical reflection on how language is politicized and canonized. Urdu, initially a product of linguistic convergence among Persian, Turkish, and Hindi-speaking communities, gained prominence as the lingua franca of the elite literary circles in South Asia. However, effects of colonialism and the hegemonic establishment of English as the language of the ‘well-read’ class, disregarded Urdu’s status within modern discourses and it now finds itself marginalized in certain educational and social frameworks in Pakistan, particularly in contrast to English and regional vernaculars.2 In this light and with Muhammad’s own experiences, his act of repurposing Urdu becomes an act of cultural preservation and resistance, suggesting that even discarded fragments can be reactivated into powerful visual statements.

Ghulam Muhammad’s artistic practice is deeply rooted in a rigorous material process that transforms language into form, and form into concept. Working primarily with paper collage on wasli, a traditional hand-made paper historically used in South Asian miniature painting, Muhammad engages in a painstaking act of collecting, cutting, and reassembling fragments of Urdu text sourced from old and discarded books. His process begins with archival excavation: scouring second-hand book markets in Lahore, he salvages printed materials that are often linguistically or culturally obsolete. These texts, often overlooked or discarded, are imbued with historical, literary, or educational significance, and their repurposing becomes a central gesture of both archival recovery and symbolic reanimation.

While the first gesture in Mohammad’s process is destruction, the second is resurrection. These tiny fragments of text are layered into visual compositions on wasli paper, often recalling natural forms, calligraphic textures, or abstract landscapes. Here, the emphasis shifts from content to presence, from narration to materiality. This recontextualization proposes that text itself can be a network of signs without a fixed origin. Mohammad constructs his images from borrowed textual elements, but instead of pointing back to an authoritative voice, his compositions point outward, to absence, memory, and multiplicity.

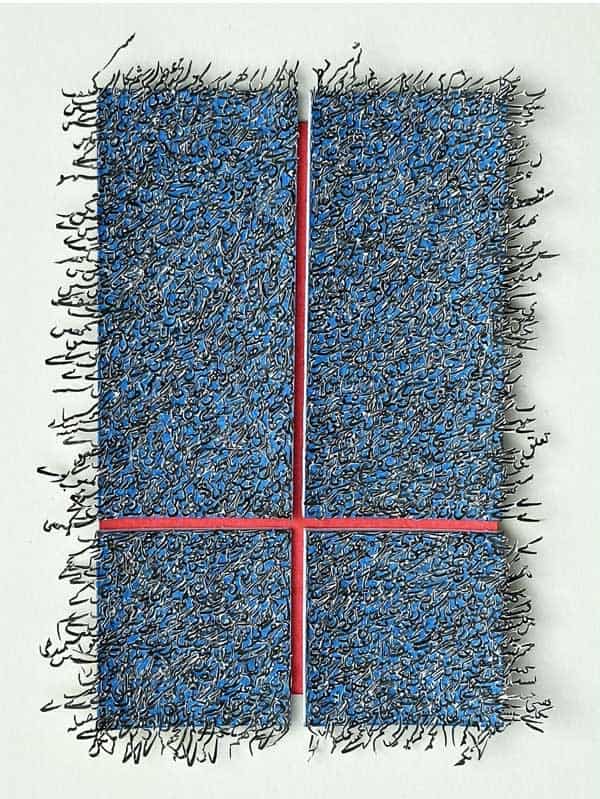

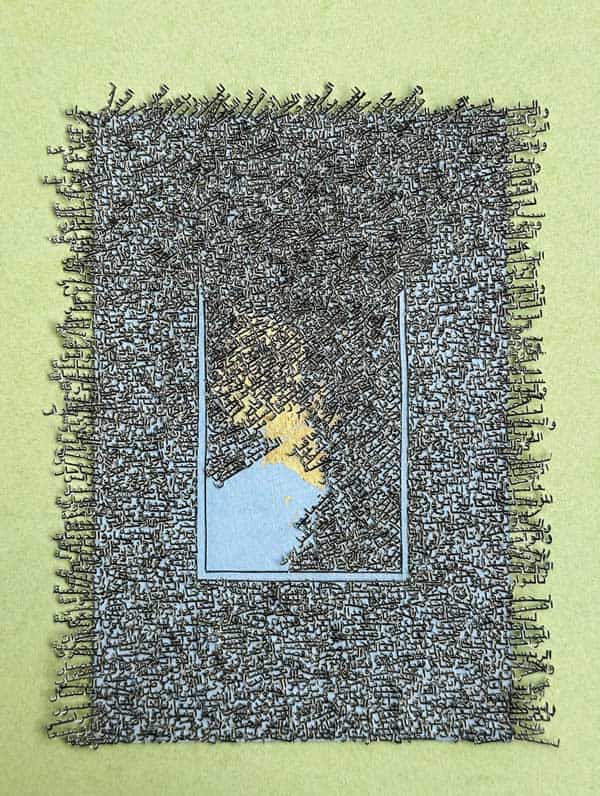

In his artwork titled ‘Ham Ahang (Compatible)’, GM assembles fragmented Urdu calligraphy into a grid-like, windowed structure divided by a red cross, reminding one of systems of order and control. However, the overflowing script challenges these boundaries, highlighting the instability and uncontainable nature of language.

The medium is as conceptually important as the text it holds. Each artwork may contain thousands of hand-cut individual Urdu letters or words, which are then meticulously reassembled into new configurations i.e. grids, vortexes, clouds, or fragmented landscapes. These arrangements often deny semantic legibility, emphasizing the visual form of the text rather than its linguistic function. This act of deconstruction and reassembly aligns with Derrida’s concepts of textuality, particularly the idea that meaning is always in flux, never fixed, and always subject to displacement.3

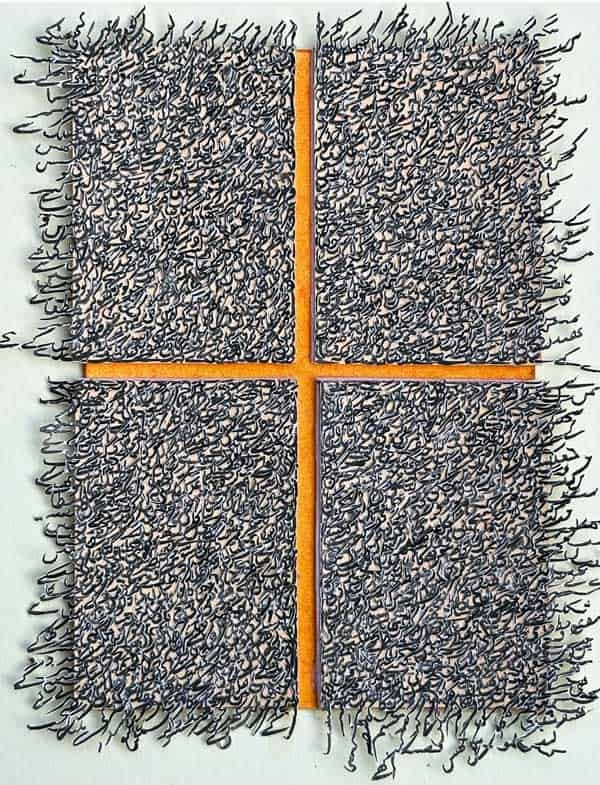

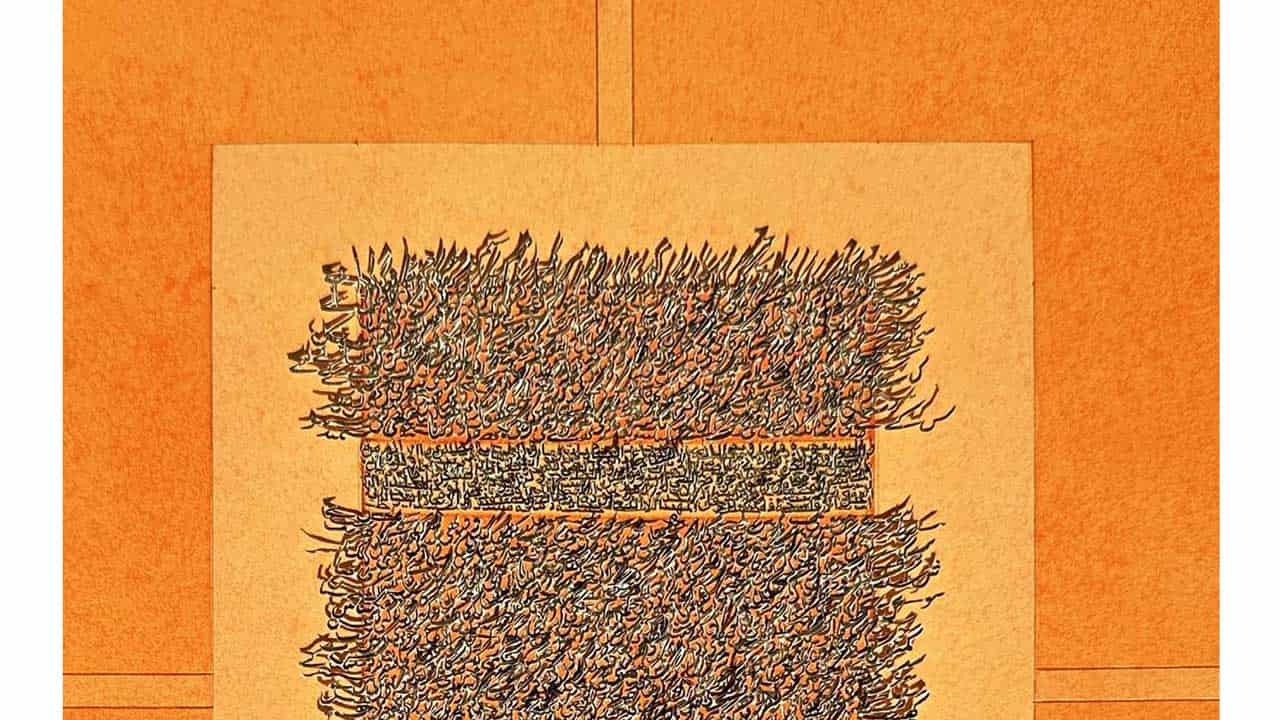

In another collage from the same exhibition titled ‘Distribution’, Muhammad continues his grid-based structure but softens its rigidity with a muted orange cross, subtly citing systems of classification and control. The swirling, organic Urdu calligraphic fragments defy these imposed boundaries, suggesting resistance to bureaucratic and colonial modes of organizing knowledge. The title Distribution becomes crucial. It not only alludes to the way letters or fragments are spread across the visual field but also resonates with ideas of knowledge dissemination, social hierarchy, and even spiritual scattering. The quadrant structures, similar to the Chahar Bagh4 concept in the Mughal architecture, may hint at the way colonial power once classified and distributed knowledge, especially through linguistic imperialism. By visually scattering Urdu text across this imposed form, Muhammad reclaims control over the distribution of language itself.

In transforming text into image, Mohammad also critiques how language structures cultural inclusion and exclusion. His work asks: Who has the right to language? Who decides what is legible, official, or worth preserving? In this regard, his practice aligns with decolonial aesthetics, particularly those that emphasize the recovery of silenced languages and voices through artistic intervention.5

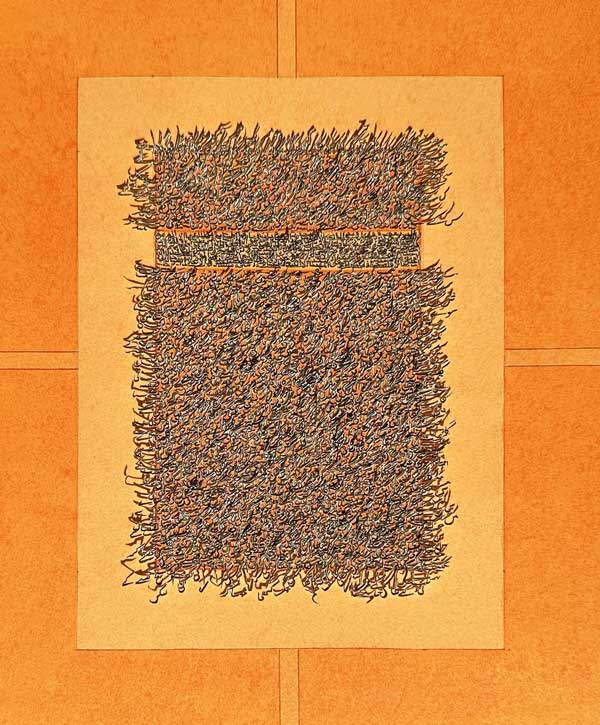

With another of his artworks, the title ‘Gardaab’ meaning “vortex”, is crucial to the interpretation. It summons not only the physical form but also the metaphorical experience of linguistic displacement, memory turbulence, and cultural fragmentation. The black-and-red contrast in the calligraphy suggests tension between erasure and assertion, where the swirling outer script appears to either erupt from or be sucked into the core. This dynamic can be read through concepts of liminality, where identities and meanings are formed in moments of transition and instability. The vortex becomes a threshold, a place where fixed linguistic identities dissolve and reconstitute.

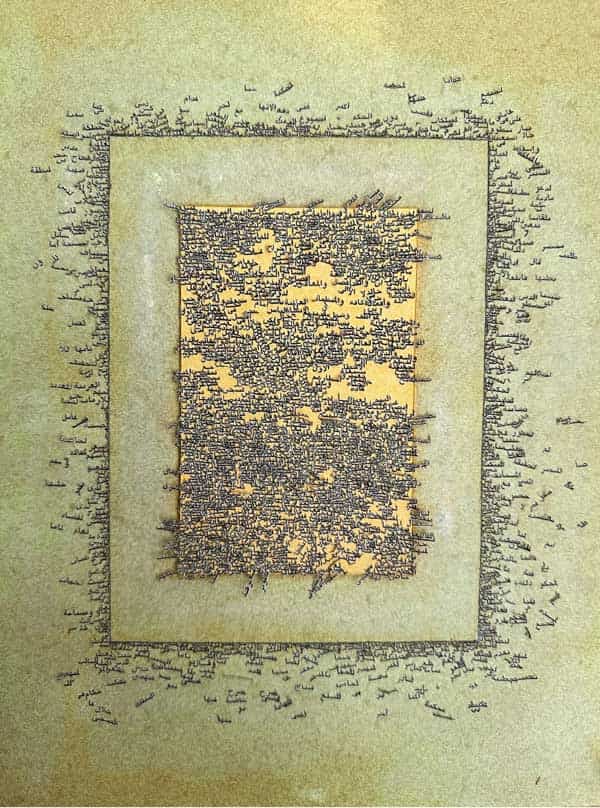

In ‘Nairang’, we witness a dense central body of Urdu words, some of which are still partially readable. This block is surrounded by scattered text particles, bleeding into the surrounding border, creating an aura-like diffusion. The visual tension between the legible center and chaotic periphery parallels the mystical relationship between knowledge and its esoteric transmission.

Muhammad’s technique also engages in what is described as the aura of the fragment, where the fragment, once removed from its original context, acquires a new poetic and philosophical potency. 6 By meticulously removing letters from one context and situating them into another, Muhammad challenges the viewer to reconsider language not as a transparent vehicle of meaning, but as a material entity with aesthetic, political, and mnemonic weight. In doing so, his process serves as a methodological metaphor for how language itself is constructed, edited, and manipulated across historical and ideological paradigms.

The labor-intensiveness of his technique becomes a critical aspect of the work. Unlike digital collage or automated printing, Muhammad’s manual engagement with paper and text is an act of devotion—a meditative resistance to the rapid consumption of information in the digital age. The physical act of hand-cutting and composing thousands of fragments echoes a scriptural intensity, blurring the lines between sacred text, personal memory, and aesthetic abstraction. In this way, his process is both political and poetic: a quiet rebellion against the erasure of linguistic identities in post-colonial contexts, and a celebration of the formal beauty of the Urdu script itself.

His work acts as a cartography of language, mapping not what words mean, but what they can become once liberated from linearity, legibility, and linguistic colonialism. This aesthetic strategy underscores that the materiality of language holds as much potential for meaning-making as its semantic function.

Ghulam Mohammad’s art speaks powerfully through what it withholds. In rendering language unreadable, he invites a deeper intervention with the material, emotional, and political dimensions of text. His works are not about storytelling in the traditional sense; rather, they are about the archaeology of language, digging through the ruins of lost books, forgotten scripts, and marginalized tongues to reveal something at once indigenous and contemporary.

The exhibition titled ‘Taleef (Compilation)’ by Ghulam Muhammad, was displayed at The Canvas Gallery, Karachi from 8th April – 17th April.

All images are courtesy of The Canvas Gallery.

- Derrida, J. Of Grammatology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Rahman, T. Language and Politics in Pakistan. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- Derrida, J. Of Grammatology.

- “Chahar Bagh” (also spelled Charbagh) is a Persian term that translates to “four gardens”. It refers to a specific style of Persian and Indo-Persian garden design, typically featuring a quadrilateral layout divided into four smaller sections by walkways or waterways.

- Mignolo, W. D. (2011). The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Benjamin, W. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In H. Arendt (Ed.), Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books.

Sumbul Natalia

Sumbul Natalia is a Lahore based visual artist, writer and researcher. She graduated in Visual Communication Design from College of Art and Design, Punjab University and holds an MPhil in Cultural Studies from the National College of Arts, Lahore. She currently serves as a lecturer in the Visual Communication Design Department at National College of Arts, Lahore and is a PhD scholar in Art and Design (studio practice) at the Punjab University. Natalia has been part of several group shows locally and internationally and has participated in various residencies and conducted curatorial projects. She regularly writes for different magazines including ArtNow, The Karachi Collective, Aleph Review, Nigaah Art, ADA magazine and The Friday Times.

There are no comments