About two decades ago, during a visit to India, I found myself at an emporium in Udaipur, Rajasthan. The space was alive with colour and devotion—walls adorned with Pichwais and other forms of Krishna-inspired devotional art, while artisans worked in quiet concentration, collaboratively painting large, intricate handloom cottons. One nearly completed Pichwai caught my eye, and I felt compelled to acquire it. My daughter, who was with me, encouraged the purchase, even though we had to wait patiently for the paint to dry. Today, that Pichwai hangs on a wall in my Karachi home, and with it began my enduring love and research for this remarkable art form.

When my artist friend Lubna Zahid— who teaches miniature and calligraphic art at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.— suggested that she, along with her writer-friend and interior designer Nabila Altaf, and I visit the Delighting Krishna exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, I was immediately enthusiastic. I happened to be in the D.C. area visiting my son and his family at the time, and the invitation felt perfectly timed.

Apparently, it was for the first time since the 1970s, that this landmark exhibition of fourteen monumental Pichwais, newly conserved, were on view from March 15 to August 24, 2025, at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Besides Pichwais, there were also several paintings of the devotional world of the Pushtimarg1, a devotional movement that emerged in northern India from the fifteenth century onward. Spanning the 18th to the 20th century, these vibrant works—- each approximately 8 by 8 feet—have never before been shown together in public. These Pichwais are more than decorative textiles; they are devotional portals.

The exhibition unfolds through a sequence of carefully curated galleries, each crafted to immerse visitors in the sensory experience of Pushtimarg devotion. Deep indigo walls and dramatic lighting evoke the intimate ambiance of Nathdwara2’s temple interiors, while the soft strains of Indian flute and drum music— recalling Krishna’s beloved bansuri— fill the air. Throughout the space, projected motifs such as lotuses, fish, and stylized hands subtly lead visitors along a path of visual and spiritual discovery.

Over the course of millennia, stories of Krishna as a playful youth, divine being, and loyal charioteer have been deeply embedded in India’s cultural consciousness. Krishna served as a charioteer for the warrior prince Arjun in the epic Mahabharata. Though Krishna was a powerful deity, he vowed not to take up arms in the war. Instead, he offered his guidance— and Arjun chose Krishna himself over Krishna’s army. As Arjuna’s charioteer, Krishna did far more than steer the horses. He became Arjun’s spiritual guide, delivering the Bhagavad Gita, a foundational text of Hindu philosophy, in which he taught the principles of duty, devotion, and righteousness. His role symbolised the idea that the divine can guide the soul through life’s moral and spiritual dilemmas, much like a charioteer guides a chariot.

Krishna is believed to have spent his childhood and youth in Braj (or Brindavan), which is the sacred region in northern India where he engaged in divine pastimes with the gopis. Centered around Vrindavan, Mathura, Gokul, and nearby villages, Braj is revered as the land of love, devotion, and divine play. It’s both a geographic region and a mythic, devotional landscape, evoked in poetry, painting, pilgrimage, and ritual.

Founded in the 16th century by a devotee, sage and philosopher Vallabha (1479–1531), the Pushtimarg (Path of Grace) centres on bhakti (loving devotion) to Krishna, especially in his child form, Shrinathji. In the Pushtimarg tradition, devotees seek not to renounce the world, but to sanctify it through joyful acts of seva (loving service): feeding, dressing, and adorning Krishna in rituals that mirror the rhythms of divine childhood.

In the centuries that followed, illustrated manuscripts of Hindu scriptures and courtly poetry centred on Krishna gained popularity. These richly coloured folios brought to life Krishna’s human relationships using pigments derived from minerals like cinnabar, metals such as gold, and natural materials like indigo. Since manuscripts intended for Hindu patrons were typically unbound, their individual pages were easily scattered— and many now reside in collections across the world. Produced over a span of 300 years— from the 1520s to the 1820s— these artworks of devotion: the endearing infant, the mischievous boy, and the graceful young lover, offer intimate glimpses into Krishna’s connections with his family, companions, and beloveds.

The Pichwai Tradition

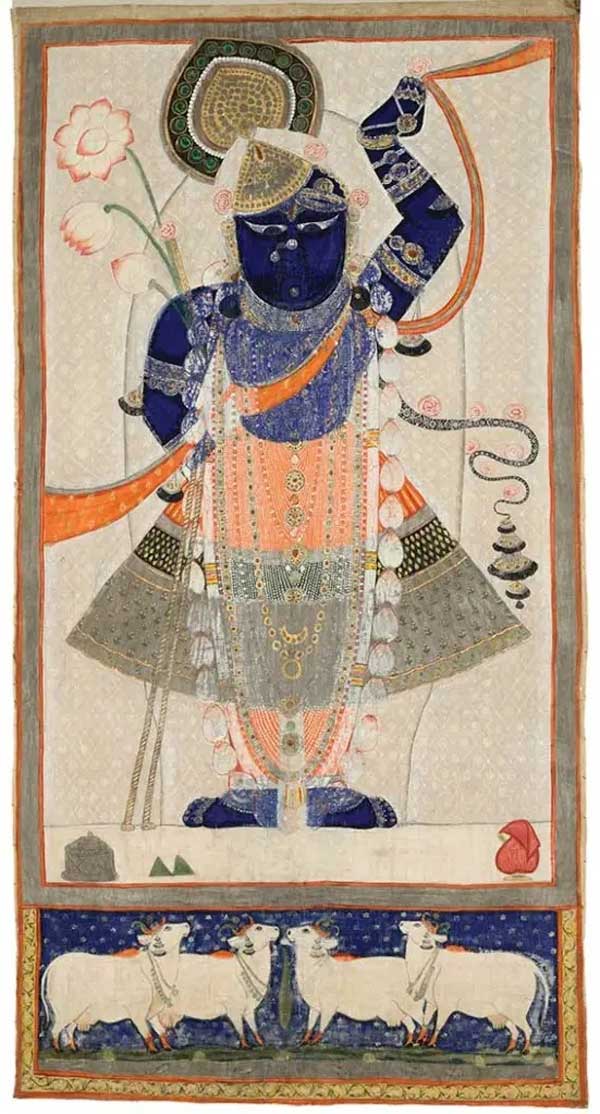

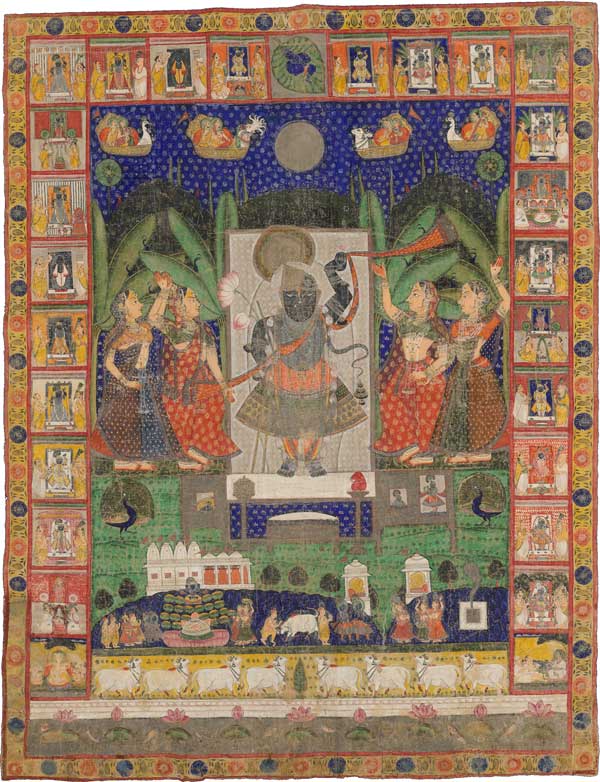

At the heart of this devotional expression are Pichwais— monumental textile paintings that serve as elaborate backdrops in temples dedicated to Shrinathji. The word Pichwai comes from the Hindi for “that which hangs at the back,” referring to their role in temple sanctuaries. These works are painted on cotton or silk, often using natural stone pigments, opaque watercolour, gold leaf, and occasionally adorned with embroidery, tinsel, or lace. They are hung behind icons of Krishna, transforming the temple into a multisensory space alive with colour, fragrance, music, and sacred imagery.

In addition to the Pichwais, the exhibition includes selected works from the museum’s South Asian and Himalayan collections, as well as those that are gifted by Karl B. Mann, a Chicago-born artist and former interior designer who, beginning in 1969, travelled frequently to India, collecting Krishna temple paintings and hangings. Moreover, there are Pichwais and paintings from the collection of my own friend— collector-archivist, and author of South Asian art, Dr Kenneth X Robbins— and his wife Joyce Robbins. Together, these works offer a layered understanding of Krishna’s cultural and devotional significance across centuries.

Pichwais created primarily in Nathdwara, Rajasthan, the spiritual and artistic heart of the Pushtimarg movement portray Krishna’s childhood episodes from the years when he lived on earth in a cowherders’ village. All were made to delight Krishna and to engage devotees’ emotions.

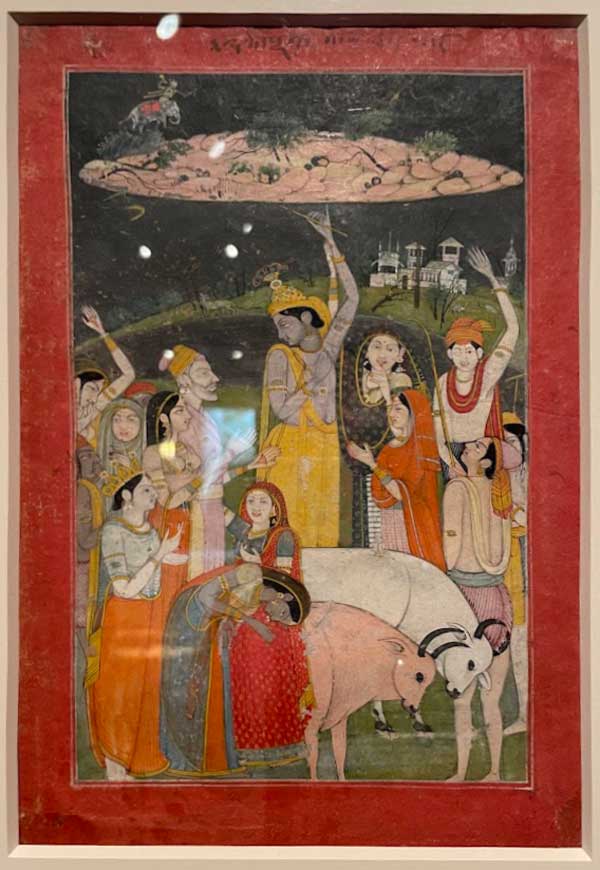

For example the pichawai, ’Krishna as Shri Nathji Lifting Mount Govardhan’ to shelter villagers from God Indra’s storm. The painting shows Indra riding his elephant across the dark sky, unleashing a torrential storm. To protect his beloved friends and family, Krishna easily lifted Mount Govardhan and balanced it atop his pinkie finger! After seven days, Indra admitted defeat, and the villagers recognised Krishna as their god.

A ‘Hide and Seek’ Pichwai depicts the mischievous disappearance of Krishna after dancing with the gopis. The bereft women, pale in the moonlight, desperately searched for him. By mixing all his pigments with white, the painter evokes a landscape illuminated by moonbeams. The gopis’ yearning for Krishna is a spiritually significant metaphor. It conveys an individual with the divine.

Gopi is the feminine form of “Gopa,” which means cowherd or protector of cows. So, Gopi literally means female cowherd. In Hindu mythology, Gopis are the devoted female followers of Lord Krishna. They are revered for their unconditional love and devotion (bhakti) towards Krishna. Among all the Gopis, Radha is considered the most beloved and spiritually significant. She is the eternal consort and spiritual counterpart of Krishna, embodying the soul’s purest devotion and longing for union with the divine. Radha represents the highest form of love (prema bhakti)— selfless, intense, and transcendental.

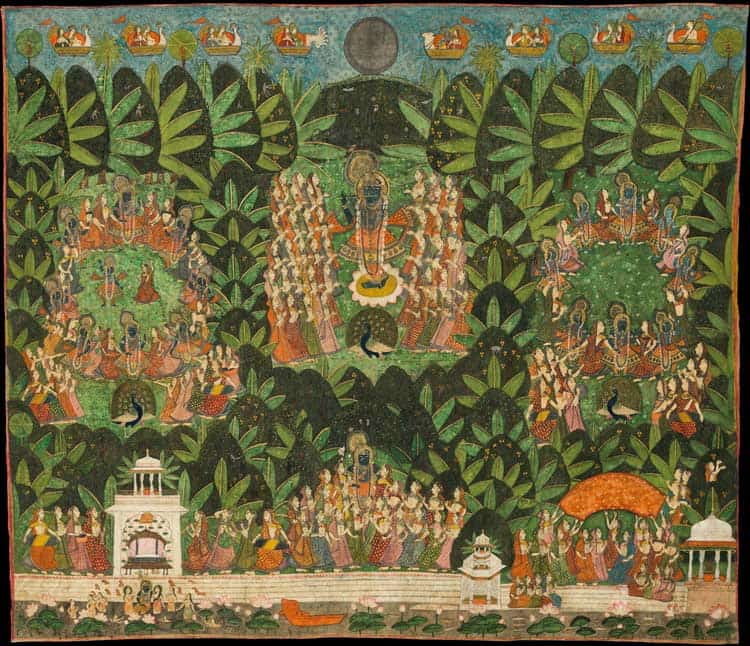

One prominent Pichwai, ‘Sharad Purnima: The Autumn Full Moon’ depicts a starry, full-moon night, with the milkmaids (gopis) on either side of Shri Nathji, whose raised arm, echoed by the postures of the gopis, seems a gesture of dance. A bright orange scarf, tucked into Krishna’s hand, unfurls to connect shrine and grove, and to him with the gopis, in a spirit of play and delight.

A rich tapestry displayed at the exhibition, ‘Raas Lila: The Divine Dance’ is the subject of many Pichwai paintings, depicting the celestial dance. In Indian aesthetics, rasa is the emotional flavour or essence; lila is play or cosmic drama. It is a Sanskrit term. While all Krishna’s actions are Lila, the most magical one occurred on the night of Sharad Purnima. That evening, Krishna, playing his flute, and beckoned the gopis to the enchanted forest of Braj. When they arrived, he multiplied himself for each gopi and joined them in the great circle dance— the Raas Lila. In the bottom far left of the Pichwai, Krishna is responding to the steadfast devotion of the gopis by joining them in the river, rejoicing and bathing, after he has seen them re-enact his lifting of Mount Govardhan.

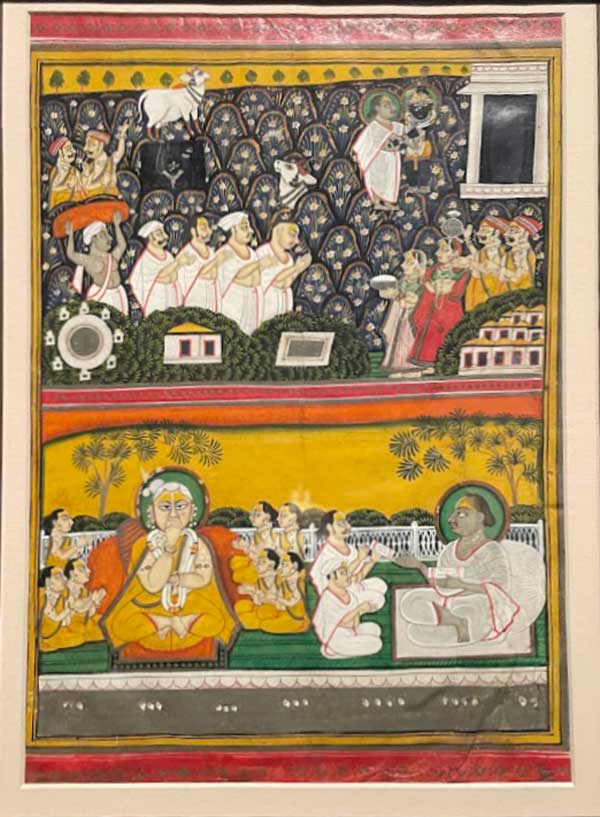

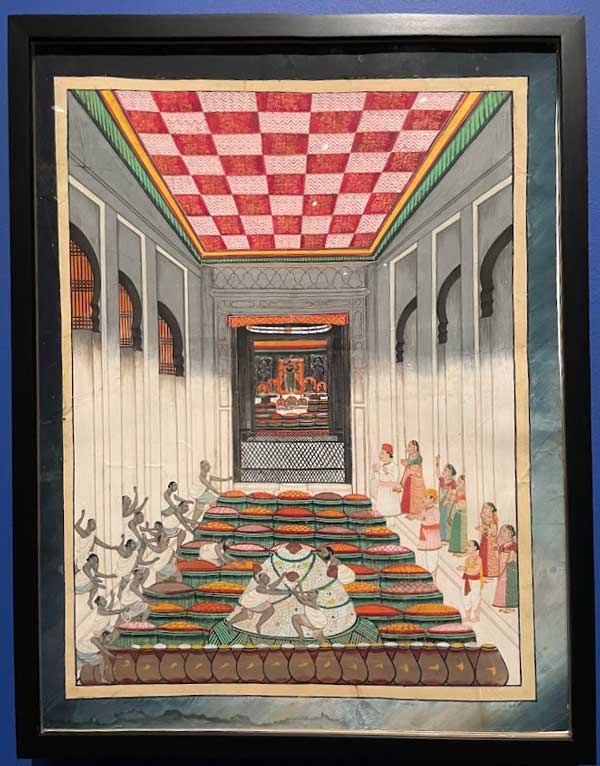

Since photographs are not allowed in Pushtimarg temples, paintings are unparalleled records of historical practices. In ‘Shri Nathji at Home’ deep perspective emphasises the grandeur of Shri Nathji’s temple and invites us to imagine the sensorial experience of its daily rituals. In the foreground are shown musicians singing verses specially chosen to evoke the mood of an event in Krishna’s youth. The setting is the haveli architecture of Nathdwara— with jharokhas,3 chatris4, corridors— venue of a domestic and devotional interior.

Similarly, ‘Morning in the Haveli’ is an artist’s depiction of morning’s activities of gently waking and clothing Krishna: an elaborate affair. He has been garbed, and a spiritual leader holds a mirror so the god can see his own appearance. The lotus pool represents the Yamuna River. Small models of cows and gopis evoke Krishna’s childhood home in Braj. The man in pink standing to the left of the pool is perhaps the devotee who commissioned this painting.

’Sharing the Rice Mountain’ is an artwork on paper that recreates the Festival of Annakut, in which the villagers of Braj cooked a feast for Krishna after he protected them from the god Indra’s torrential storms. Fifty-six vegetarian delicacies and a massive heap of boiled rice are prepared as offerings. Often Shrinathji is shown in the front, possibly raising the “mountain” of rice in his hand— signifying divine generosity.

A fascinating aspect of these devotional artworks is the souvenir tradition pioneered by artists Khubiram and Gopilal in their Nathdwara studio, established in 1907. They developed a unique process in which each pilgrim’s portrait was individually photographed, cut into small squares, and affixed to the canvas before the rest of the scene was painted around them. This personalised devotional practice is beautifully exemplified in ‘Creating a Memory: A Family Worshipping Shri Nathji’.

Krishna is often shown reaching into pots of butter, surrounded by gopis or with his mother Yashoda, capturing the charm and spiritual playfulness of his childhood. He is lovingly also called “Makhan Chor” (Butter Thief). His childhood tales show Krishna stealing freshly churned butter from Yashoda and the homes of the gopis in Vrindavan. Butter represents the sweet essence of devotion, churned from the heart— Krishna, as the divine, eagerly seeks this purest offering, and his playful thefts highlight the intimacy and joy of the bhakti (devotional) relationship between God and devotee. They also underscore his role as the divine child, mischievous yet beloved, who breaks rules only to bind hearts.

In Pushtimarg homes, Krishna takes the form of a small, crawling toddler who is referred to as a Lalan (beloved). At the exhibition, there are hardly any three-dimensional pieces, but ‘Replica of a Lalan’ is one such exception, dressed by siblings Kesar and Kush Patel, who came to the museum in February 2025, to adorn the dark baby Krishna in yellow garments, a peacock-feather crown, and lots of jewellery.

In paintings too, Krishna is often shown in shades of blue and black, symbolising eternity, calmness, and transcendence. His very name means “dark”, “black” or “all-attractive” in Sanskrit. So Krishna is dark not just in appearance, but in the rich poetic, philosophical, and devotional sense he is the mystery that draws the heart, the divine presence that both conceals and reveals.

It is pertinent to mention the role of the famous pioneering Indian artist, Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906), who played a transformative role in shaping how Krishna was visually imagined in the modern era— particularly through mass-produced chromolithograph prints of his paintings. In 1894, Ravi Varma established the Ravi Varma Fine Art Lithographic Press in Bombay to reproduce his paintings as affordable prints for wide distribution. This democratised religious imagery, making Krishna’s image accessible to middle-class homes across India—no longer confined to temples or manuscripts.

The exhibition is a five-year initiative supported by the Lilly Endowment that seeks to deepen civic dialogue and broaden public understanding of religion through The Arts of Devotion. While the Endowment’s support has traditionally focused on Christian contexts, this initiative expands its scope to include Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic visual cultures. The museum’s three-year conservation initiative has uncovered vital insights into the materials, techniques, and artistic brilliance of Pichwai painters— from pigment composition to the structure of cotton supports— shedding new light on the ingenuity behind these devotional works. Delighting Krishna, with its rich blend of historical research, artistic mastery, and living tradition, invites visitors into a world where art and devotion are inseparable. Awash with color, rhythm, and deep emotional resonance, the exhibition not only celebrates one of Hinduism’s most cherished devotional practices but also reaffirms that sacred art continues to evolve, enchant, and inspire across time.

Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art Presented “Delighting Krishna: Paintings of the Child-God” which was on display from March 15–August 24, 2025

Title Image: Delighting Krishna: Paintings of the Child God, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Museum, Washington DC.

Images courtesy of Rumana Husain, and National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Museum, Washington DC

- Pushtimarg, meaning “Path of Grace,” is a Vaishnav tradition within Hinduism founded by Shri Vallabhacharya around the late 15th century. It emphasizes spontaneous, selfless love for Shri Krishna and the direct experience of God’s grace, not through suppression of worldly desires but by diverting them towards Krishna. The path is centered on devotional practices like seva (service), and it allows householders to maintain their lives while serving God.

- The city of Nathdwara, in the Rajsamand district of the state of Rajasthan, India, is famous for being the residence of Lord Shrinathji, who is considered the “swaroop” or incarnation of infant Lord Krishna.

- An architectural element from medieval Indian architecture, specifically a projected window or balcony, typically from an upper story of a building, that overlooks a street, market, or other public space.

- An elevated, dome-shaped pavilion or kiosk with intricate carvings, a traditional element of Indian architecture that literally means “umbrella”.

Rumana Husain

Rumana Husain is a dedicated author, art critic, artist, and educator, who has made significant contributions to storytelling, art, and social impact. She served as the co-founding Senior Editor of NuktaArt magazine from 2004 to 2014. She has written two critically acclaimed coffee-table books detailing the lives of Karachi's inhabitants, and is the author and illustrator of over 90 children's books, with four of them winning awards in Pakistan, Nepal, and India. Furthermore, she has authored hundreds of articles, travelogues, and reviews for various national newspapers and magazines.

There are no comments